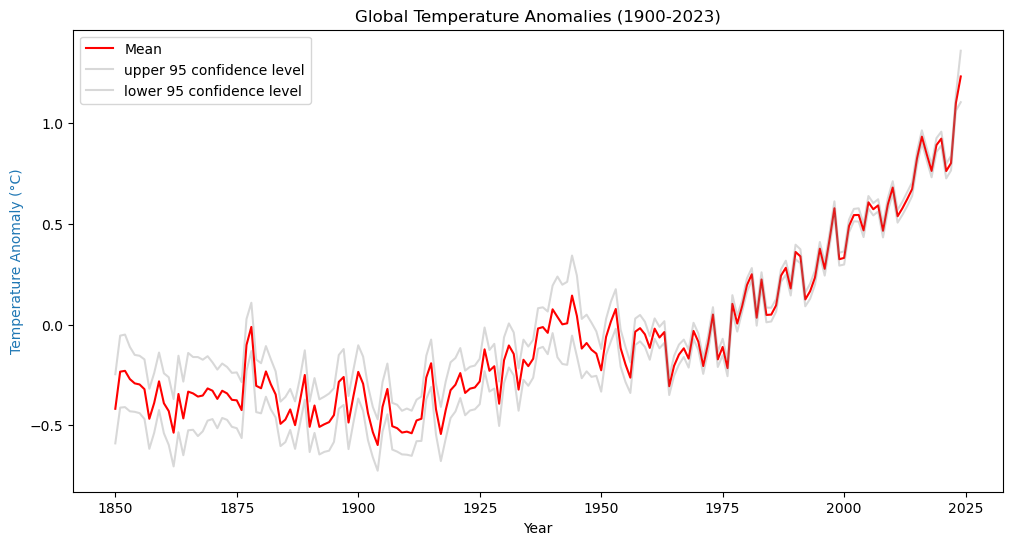

The global mean temperature has demonstrably increased by over 1.0 °C since the pre-industrial baseline, with the warmest years overwhelmingly clustered in the 21st century. This rise is statistically robust and well outside the range of natural climate variability, signifying a substantial and rapid shift in the Earth's climate system.

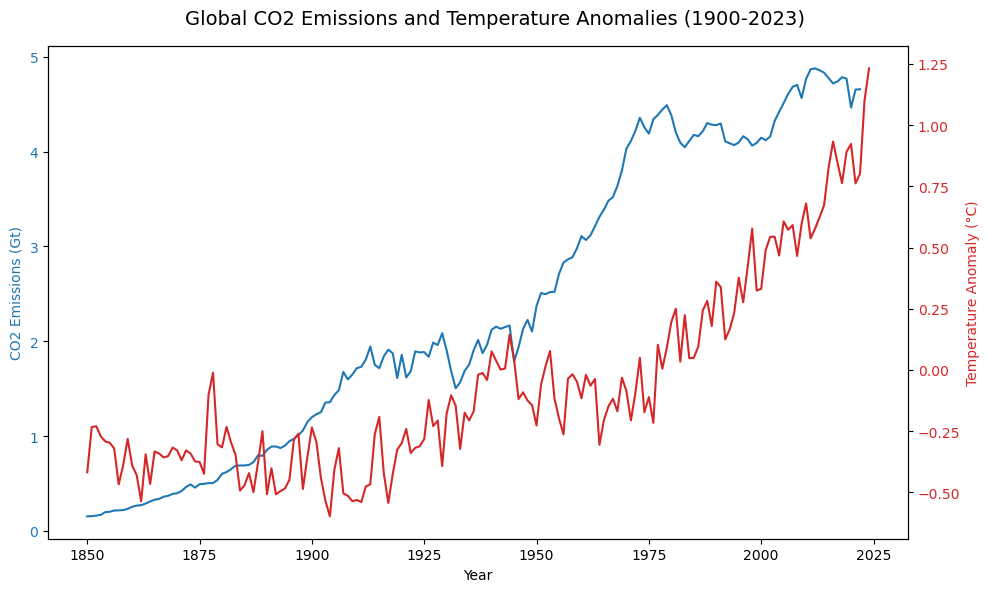

As the figure below reveals, CO₂ is the principal driver behind this warming. It shows a compelling link where the sharp, sustained increase in anthropogenic CO₂ emissions (blue line) is mirrored by the accelerating rise in the global temperature anomaly (red line). This correlation confirms the foundational climate science: increased human-caused CO₂ traps more heat, enhancing the greenhouse effect, and is the primary forcing agent responsible for the dangerous warming trend now observed globally.

Financial authorities and banks increasingly treat climate as a driver of financial risk—not a separate category. Observed concentrations of atmospheric CO₂ continue to set new highs, reinforcing physical-change trajectories (physical risk) and policy responses (transition risk) that can affect asset prices, borrower cash flows, and collateral values.

Scenarios developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) are now standard practice for both central banks and the private sector to evaluate macro-financial pathways concerning orderly versus disorderly transitions and associated physical risks.

Transition Risk refers to the potential challenges associated with policy and regulatory changes, such as carbon pricing and new standards, as well as shifts in technology (e.g., the move toward electrification) and changes in demand. These factors can affect the revenue mix, operating and capital expenditures, the risk of asset stranding, and the cost of financing.

Physical Risk includes acute hazards, like floods, wildfires, and heatwaves, as well as chronic hazards such as sea-level rise, heat stress, and drought. These risks can damage assets, disrupt operations and supply chains, and reduce productivity.

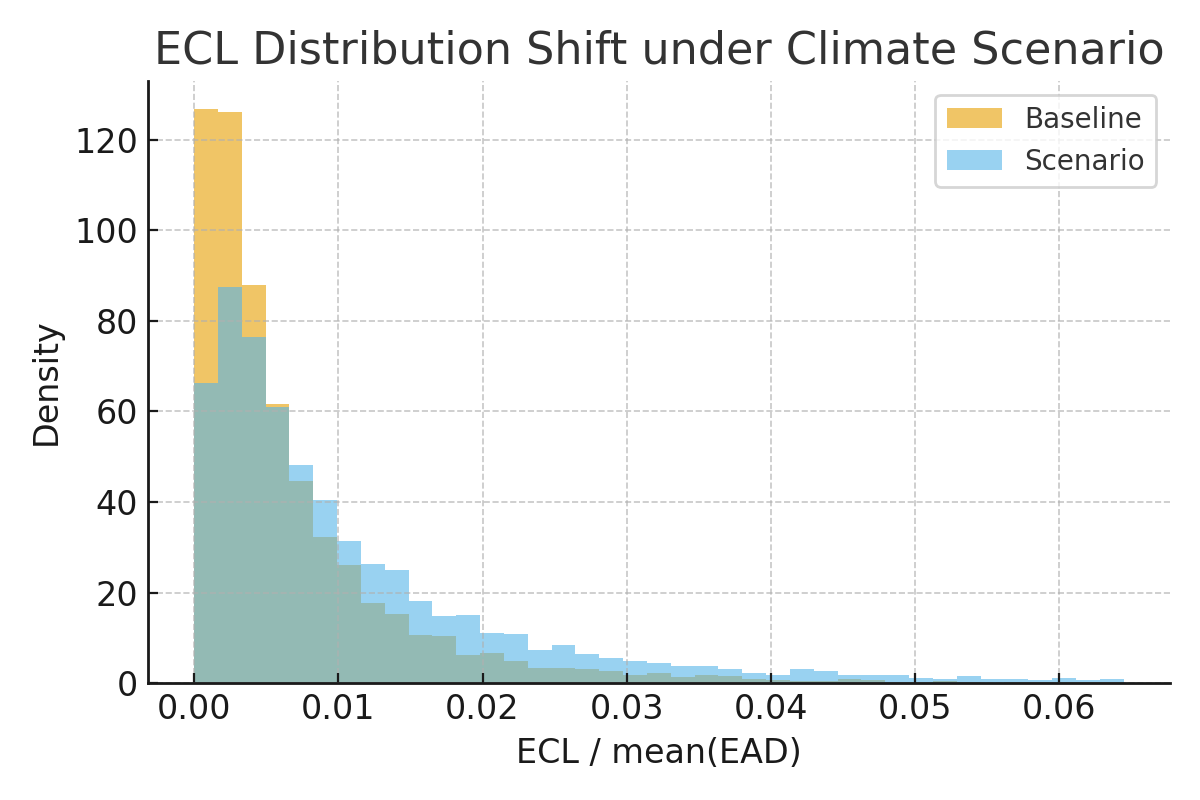

Credit Risk:

The probability of default (PD) is influenced by factors such as earnings stress, leverage, and the risk of stranded assets. Loss given default (LGD) is affected by the impairment of collateral and its marketability. Exposure at default (EAD) is impacted by potential drawdowns and covenants.

The illustrative simulation shows ECL rising as PD and LGD adjust for carbon intensity and hazard exposure. This demonstrates how banks’ expected credit losses can increase under NGFS disorderly-transition scenarios.

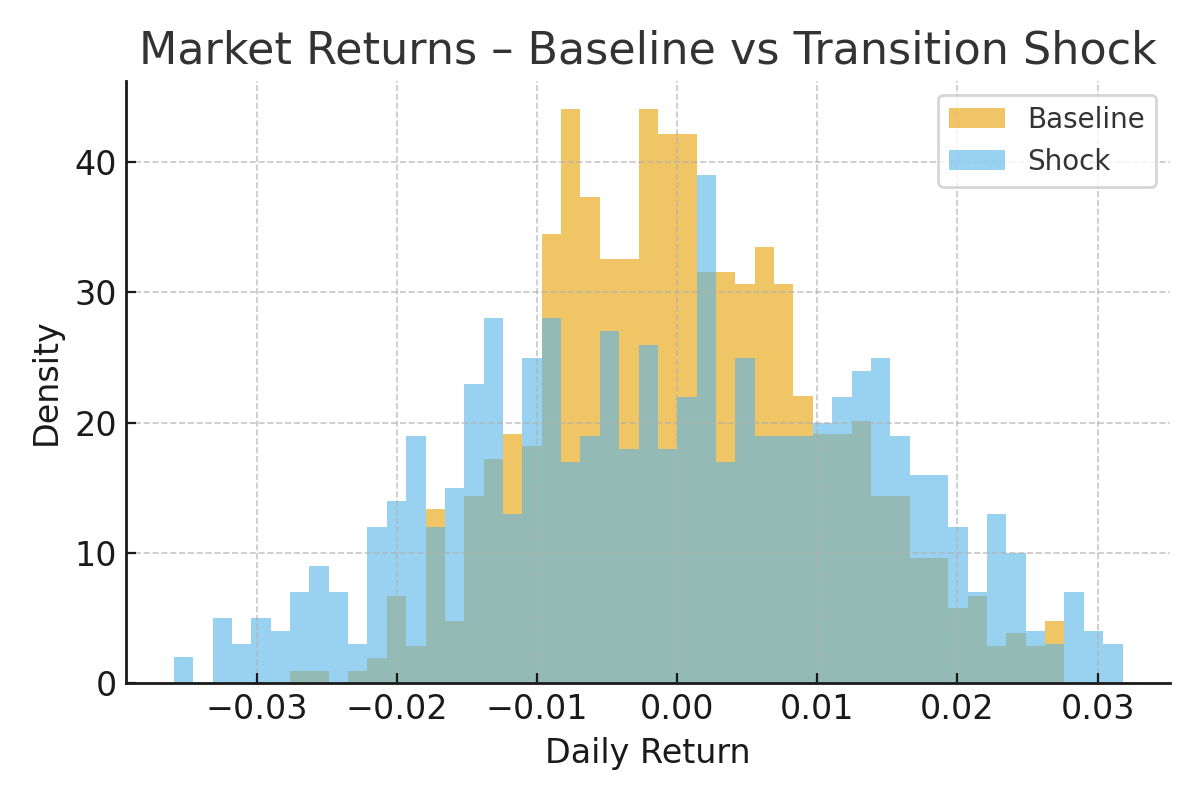

Market Risk:

Market risk-related parameters such as price volatility and return distributions can change through the repricing of carbon-intensive exposures, shifts in factor tilts, and liquidity considerations.

The figure below illustrates how left-tail risk increases under a transition shock. This trend corresponds with market behavior following abrupt policy or energy shocks.

Regulators are increasingly quantifying the near-term macroeconomic impacts of extreme events. For example, a recent assessment by European supervisors suggests that we could see around a 5% decline in GDP in the event of a severe sequence of disasters, assuming there is no effective policy response.

In the UAE and GCC, transition risk primarily arises from exposure to hydrocarbons, while physical risk is mainly associated with heat and flood hazards. Portfolio analysis should focus on the following areas:

- Credit exposures in the energy, real estate, and transportation sectors.

- Collateral located in coastal areas (such as Dubai and the Abu Dhabi Corniche) that is vulnerable to rising sea levels.

- The adaptation capacity of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and corporations, as well as relevant policy incentives, such as the UAE's Net Zero 2050 initiative.

Banks should incorporate climate scenarios into their ICAAP and stress testing, linking NGFS pathways to key UAE macroeconomic variables like non-oil GDP, real estate prices, and inflation. Market risk metrics should account for carbon price shocks and liquidity stress, while credit risk models must include PD and LGD adjustments that reflect transition and physical risks.